Occasionally, we see images of blacksmiths on TV.

When we think of blacksmiths, we often imagine scenes of heating metal, hammering it, and then cooling it in water. This process is the foundation of what we call heat treatment.

In this process, the act of heating the steel and cooling it rapidly in water is known as quenching. It’s a method that has been used for centuries to harden steel.

Quenching involves heating the steel until it glows red and then cooling it rapidly—this heating is referred to as austenitizing, and the cooling is known as quenching or rapid cooling.

There are two critical rules that must be followed for proper quenching to harden the steel:

- The temperature must exceed 730°C, also known as the A1 point. If even 1°C short, no matter how skilled the technician is, the steel will not harden.

- The cooling must be as rapid as possible, usually by immersing the steel in water or oil.

Once the steel passes 730°C, its internal structure begins to transform rapidly.

In other words, a phase transformation occurs.

The steel’s internal structure changes from pearlite to austenite.

If the austenite is then cooled quickly, it transforms again into martensite.

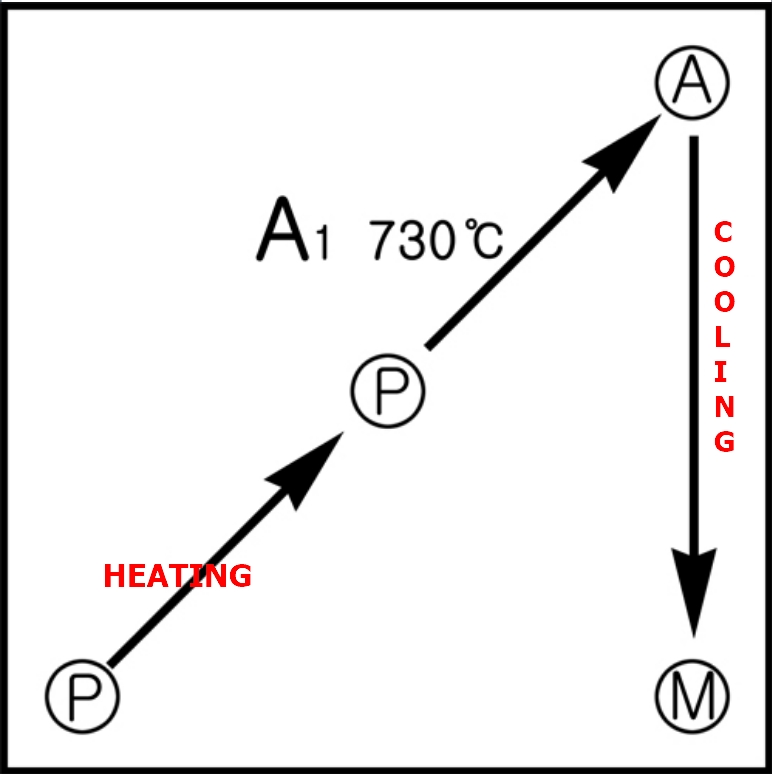

This means, as shown in the diagram, the structure of the steel changes:

Put simply, quenching is the process of transforming pearlite (P) into austenite (A) through heating, and then into martensite (M) through rapid cooling.

This heat treatment requires both heating and cooling, and without going through austenite, martensite cannot be formed from pearlite.

So, if the temperature doesn’t exceed 730°C, even if it’s just 1°C short, quenching in water or oil won’t make the steel harder. Instead, it will revert to a soft pearlite structure.

Among the steel structures, martensite is the hardest and most costly to produce, austenite is the softest, and pearlite is in between.

Therefore, when quenching is successful, the steel hardens and expands. This is why, when making something like a Japanese sword in a forge, it bends as it hardens.

Although quenching usually hardens steel, some types of steel can become hard just by slowly cooling in air instead of rapid cooling. These are called air-hardening steels.

Conversely, some steels do not harden even with rapid cooling in water, and instead become softer and more ductile.

One such steel is high-manganese steel (1% C, 13% Mn). Even when heated to austenite and then rapidly cooled, it does not transform into martensite—it remains as austenite.

This process is not called quenching but solution treating.

In this case, the steel does not harden but rather gains toughness and ductility.

Similarly, 18-8 stainless steel, which is non-magnetic, will also not form martensite when rapidly cooled in water. Instead, it becomes fully austenitic and does not harden.

This, too, is a kind of solution treatment, typically called solution heat treatment.

While these types of steels do not form martensite when water-quenched, if mechanical force is applied—such as hammering or aggressive machining—and then rapidly cooled, they may transform into martensite more easily.

This is why, although high-manganese steels and stainless steels may appear soft, they are often more difficult to machine.

In summary, although quenching generally causes steel to form martensite and become hard, it’s important to remember that some steels, like high-manganese or stainless steels, remain austenitic and do not harden through this process.

Dyna Co., Ltd.

Industrial Lubricant Solution

E-Mail : dyna@dynachem.co.kr

Web : dyna.co.kr/en/

댓글 남기기